Geography and scale

The Occupied Palestinian Territories are comprised of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. Bordering Gaza is Egypt on the southwest, Israel on the south, east and north, and the Mediterranean Sea on the Eastern coast. The West Bank, with which this research project is concerned, borders Israel on the west, north and south, and Jordan on the East. Although the West Bank is shrinking in size with Israel’s continuing land grab, in 2003 it was calculated as covering a land mass area of 5,860 sq km (Land: 5,640 sq km and water: 220 sq km). Comparatively, the total area is a quarter of the size of Wales. A landscape made up of rugged terrain, dissected upland with some vegetation in the west, barren in the east and a dramatic desert scape in the south, the lowest point is the Dead Sea at 408 m below sea level and the highest point Asur at 1,022 m. (1)

Brief History of the Region

For the indigenous people of Palestine, the Palestinians, 14 May 1948 and the events leading up to it are known as Al Naqba (The Catastrophe), referring to the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their homes and the dispossession of their land resulting in over 700,000 refugees and 418 villages destroyed. (2) Many Palestinians were forced to seek refuge in neighbouring countries like Lebanon and Jordan or to set up temporary homes in refugee camps around Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza. Sixty years later these refugee camps still exist, without any permanent status or means of applying for official building permits. The residents live in a seemingly permanent state of transience and rootlessness as they wait to return home.

Occupied by Jordan and Egypt between 1948 and 1967, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank have been under Israeli Occupation since the Six-Day War of 1967. The Israeli occupying force withdrew its settlements from Gaza in 2005 but still continues to control all borders, air and sea space.

The continuing impact of globalisation and the speed and pace with which Israel’s colonial project has progressed under its influence have created another level of exploitation which the Occupation administers within the OPT. This now includes not just the construction of settlements but also the industrialisation of the West Bank explicitly for Israel’s use and the expropriation of raw materials from its quarries.

Administration/Politics

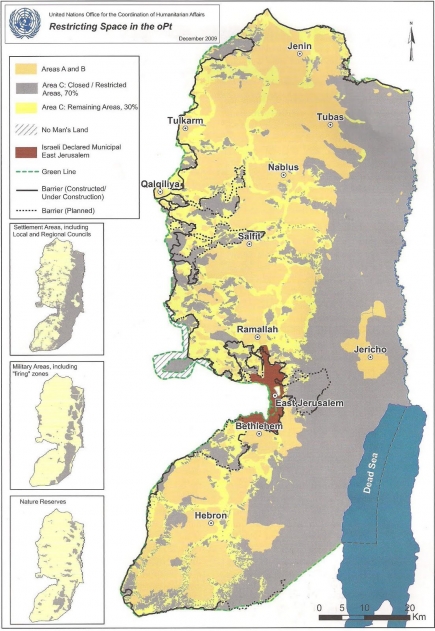

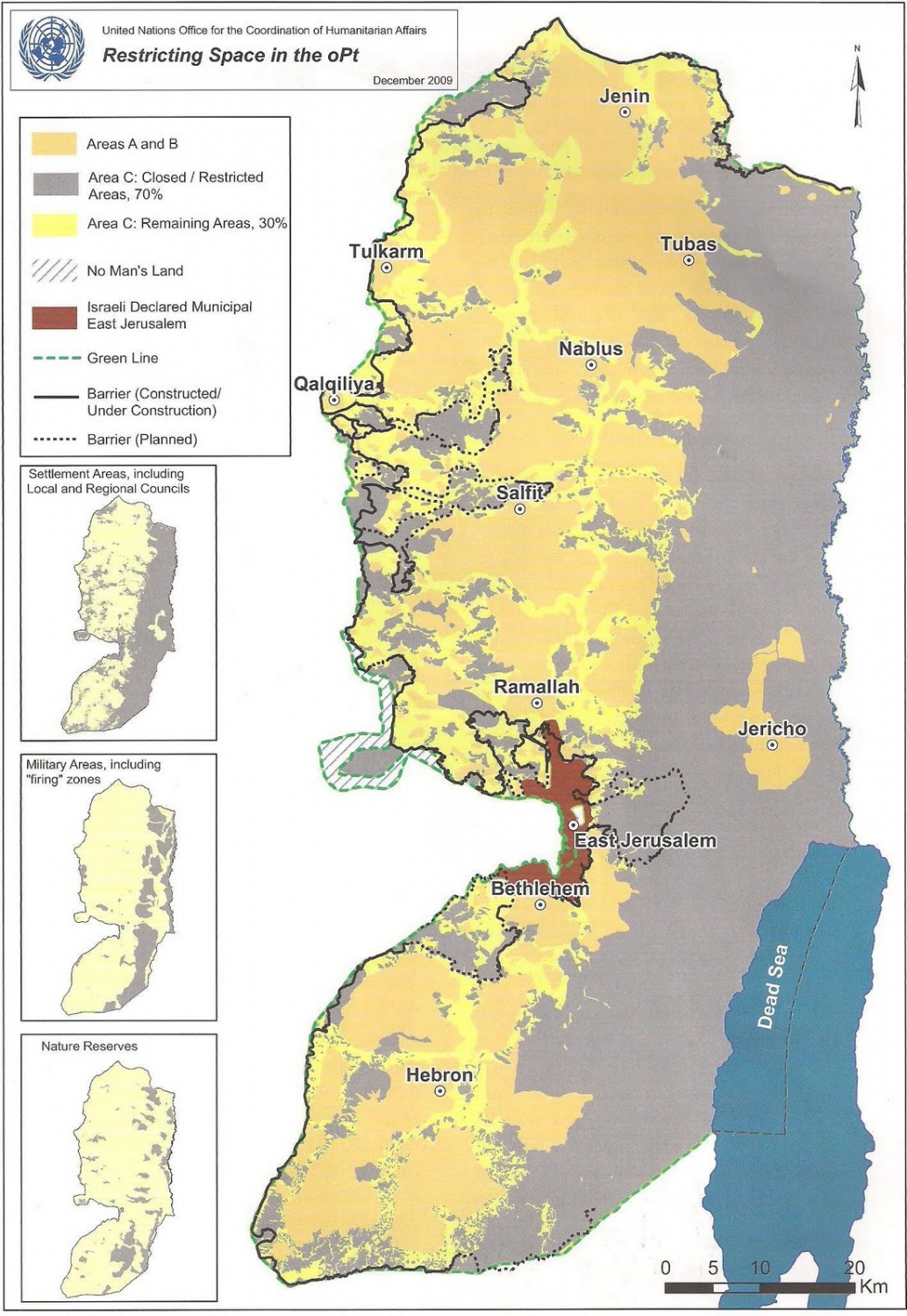

The West Bank is currently divided in terms of administration and security. There are three areas known as Area A, Area B and Area C, and these different ‘Zones’ have a different impact on Palestinians depending on the degree to which their lives are oppressed and regulated and the extent to which they are able to engage with and use space in the OPT (see figure A). The measurements given below are an approximation as the West Bank is constantly changing as Israel moves towards establishing greater control.

Area A includes most of the major Palestinian cities – Ramallah, Nablus, Bethlehem, Hebron and Jenin, is under the military and civil control of the Palestinian Authority, and amounts to approximately seventeen percent of the total area of the West Bank.

Area B contains the vast majority of Palestinian towns and is under the control of both the Israeli military and the Palestinian administration. It amounts to approximately twenty percent of the total area. (3)

Area C is under both military and administrative control by Israel and amounts to approximately sixty percent of the total area of the West Bank.

In July 2013 it was estimated that there are 2,676,740 people living in the West Bank. Palestinians make up approximately eighty-three percent, and Israeli settlers seventeen percent. There are around 325,500 Israeli settlers living in the 121 officially recognised settlements (with a further 102 unauthorised outposts in the West Bank that are not officially recognised by Israel), while 186,929 Israeli settlers live in annexed East Jerusalem. (4)

Israel retains full control over the building and planning sphere in Area C, while responsibility for the provision of services falls to the Palestinian Authority (PA). The consequences are that Palestinians are prohibited from building, working the land or setting up businesses without a permit from Israel, which is in most cases denied. As well as these divisional Areas A, B and C, the shrinking of space within the OPT has taken on a new intensity and pace over the last twenty years, since the Oslo Accords in 1993. (5)

Attempting to create a platform for future relations between Israel and Palestine, the Oslo Accords served as a framework for the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA) that would administer the Palestinian territories and the withdrawal of the Israel Occupation Force (IOF) from parts of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. In the five-year period in which the Accords lasted, during which a permanent agreement was to be negotiated, Israel continued to build and expand settlements within the Palestinian Territories while Palestinians were still denied permission to build within Zone C (60% of the territories). For many the Oslo Accords are seen as having enabled the disbandment and curtailing of the Palestinian resistance movement under the auspices of the Palestinian Authority, a political institution that has effectively been powerless in transforming the spatial, political and economic dynamics on the ground in the OPT in its negotiations with Israel for a Palestinian state with self-determination.

Contraction of space within the OPT West Bank

The contraction of space within the Palestinian Territories has been driven by a number of strategies adopted by the Occupying Force. Jeff Halper, anthropologist, political activist and co-founder and coordinator of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD), describes the spatial dynamics of the OPT as a matrix of control implemented by Israel:

For the most part the matrix relies upon subtle interventions performed under the guise of ‘proper administration,’ ‘upholding the law,’ ‘keeping the public order’ and, of course, ‘security.’ These interventions, largely bureaucratic and legal, are nevertheless backed by overwhelming military force which Israel reserves for itself the right to employ. The active, forcible measures of control which can be taken against Palestinian communities and individuals include the extensive use of collaborators and undercover ‘mustarabi’ army units, administrative detention, arrest, trial and torture. (6)

This matrix of control severely restricts the flow of movement or autonomy that the Palestinians have in the OPT. The policy of restriction includes the increasing expansion and construction of settlements, the construction of roads linking the settlements to Israel and to each other, the cutting through and defacing of Palestinian land by the Separation Wall, the direct ownership of Palestinian land by Israeli businesses, and, through all of the above, the creation of non-spaces or no-man’s-lands that separate the settlements through fenced-off perimeters. These are often placed 200–300 metres away from a settlement as a security measure and render the enclosed area untenable for agriculture, homes or businesses. The consequence of this for Palestinian farmers, olive groves and the expansion of Palestinian residential areas is enormous. It is not unusual to find the remnants of a house that stands isolated and abandoned between a settlement and a Palestinian village or town. The house will have been deemed unuseable in order to protect the Jewish settlements.

As of September 2008, there were ninety-three manned checkpoints and 533 unmanned blocks in the West Bank. (7) To some degree these checkpoints are possible to prepare for, and one can estimate the time needed to get through them. However there are also ‘surprise checkpoints’, consisting of a Jeep or armoured vehicles and a small number of soldiers. Numerous trenches, physical obstacles and temporary roadblocks are also put in place by the army to control and restrict pedestrian and vehicle traffic in the OPT, creating an even greater disruption to life than that of the permanent road blocks as it is impossible to prepare for them.

Palestinians wishing to get through the checkpoints are often subjected to unnecessary humiliations, arbitrary delays and uncompromising bureaucratic demands. In early 2001 Machsom Watch, (8) an Israeli women’s activist group, was set up to monitor and intervene in the violence and abuse at checkpoints by the military (who are mostly young men and women aged between 18–24). The watching practice, emphasised in the movement’s name, aims to challenge the checkpoint as a military-masculine space by introducing a civilian-feminist gaze. (9)

According to Eyal Weizman, the Occupation has created a fluid Israeli ‘hyper-space’ (10) in the West Bank, detached from a highly fragmented Palestinian ‘infra-space’. There is almost a complete disassociation between Israeli space and Palestinian space, created by different strata and levels as well as borders and zones. The OPT is a region lacking any real legitimacy or functional ability for Palestinians, consisting of unconnected enclaves and fragmented islands that remain as a consequence isolated topias. The architect and member of the artistic group Decolonising Architecture, Alessandro Petti, describes the system of connected islands that represent the Israeli settlements in the OPT as an archipelago where movement is fluid and rapid,(11) whereas for Palestinians, moving through the OPT involves threading through mazes and dead ends, cracks and openings.

- (1) Central Intelligence Agency, The World Fact Book, Middle East: West Bank <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/we.html> [accessed 3 September 2013].

- (2) See Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited (Cambridge University Press, 2003) and Walid Khalidi, ed., All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948 (Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992).

- (3) Elisha Efrat demonstrates that at the beginning of the 2000s, towns and villages in Area C under Israeli control constituted a continuous space, whereas Areas A and B were divided into 190 enclaves. See The Geography of Occupation (Carmel, 2003), cited in Cédric Parizot, ‘Temporalities and Perceptions of the Separation Between Israelis and Palestinians’, Bulletin du Centre de recherché français de Jérusalem, 20 (2009) <http://bcrfj.revues.org/6319> [accessed 3 September 2013] (para 24).

- (4) Central Intelligence Agency, The World Fact Book, Middle East: West Bank.

- (5) It has been noted by Edward Said and others that the signing of the Oslo Accords was on the same date as the Sabra and Shatilla massacres in Lebanon: 13 September 1982. Hundreds of Palestinians were slaughtered in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps by Lebanese Phalangists aided by the Israeli army.SeeGilles Deleuze, Gilles Deleuze and the Palestinians, trans. by Timothy Murphy (originally published in Revue d’etudes palestiniennes, September 1983),Architexturez network, Driftline: Deleuze-Guattari-L (1994) <http://mail.architexturez.net/+/Deleuze-Guattari-L/archive//msg04437.shtml> [accessed 3 September 2013].

(6) Jeff Halper,‘The 94 Percent Solution: A Matrix of Control’, Middle East Report, 216 (2000) <http://www.merip.org/mer/mer216/216_halper.html> [accessed 3 September 2013].

(7) United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘West Bank Closure Count and Analysis’ (2006) <http://unispal.un.org/pdfs/WB0106.pdf> [accessed 3 September 2013]. Machsomwatch, ‘Women Against occupation for Human Rights’ (2001) <http://www.machsomwatch.org/en> [accessed 3 September 2013].

(8) Machsomwatch, ‘Women Against occupation for Human Rights’ (2001) <http://www.machsomwatch.org/en> [accessed 3 September 2013].

(9) Ibid. The civilian-feminine gaze is explored in more depth in Chapter Five, in relation to Ariella Azouly’s work on ‘The civil contract of photography’.

(10) Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation (Verso, 2007)

(11) Alessandro Petti, ‘Asymmetries in Globalized Space: On the Border Between Jordan and Palestine-Israel’, Centre for Research Architecture <http://roundtable.kein.org/node/1111> [accessed 3 September 2013].